Fig.1

Explosives Analysis

Fig.2

Fig.3

Explosives and Chemical Unknowns

Energetic materials, often referred to as explosives, are a category of chemical evidence frequently encountered in criminal investigations. In Ireland, the Explosive Substances Act of 1883 makes it a serious felony to cause an explosion likely to endanger life or property. Legitimate uses of explosives are confined to specific contexts like civil engineering (e.g. controlled demolitions, mining) or military operations.

Criminal use of explosives can have various motives: financial gain, targeting specific individuals or organizations, inflicting social terror (as in terrorist attacks motivated by political or religious extremism), or even using bomb threats to influence behaviour. Sometimes explosives are used simply as tools, with the goal of blasting open safes or ATMs. Criminal cases involving explosives often include the illegal manufacture and trade of such materials.

- Explosive devices can be designed to produce a blast effect (destructive shockwave) or primarily an incendiary effect (to start fires), or both. In forensic analysis, explosives are often classified by their reaction speed and effects:

- High explosives: React extremely quickly (detonate), produce shockwave. Examples: TNT, PETN, and ammonium nitrate-fuel oil (ANFO).

- Low explosives: Burn rapidly (deflagrate) rather than detonate and usually need to be confined i.e. in a pipe bomb. Examples: black powder, smokeless powder, and pyrotechnic mixtures found in fireworks.

- Incendiary mixtures: Some devices are designed to start fires using flammable substances (like petrol or other accelerants) rather than to explode with force. Examples: firebombs, napalm, Molotov cocktail.

The laboratory utilizes a wide array of analytical instruments to characterize explosive substances. Such instrumentation includes Fourier Transform Infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR), micro X-ray fluorescence (µXRF), scanning electron microscopy (SEM), and Gas Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS), and ion chromatography (IC). These tools allow detection of organic and inorganic explosive compounds present in a sample.

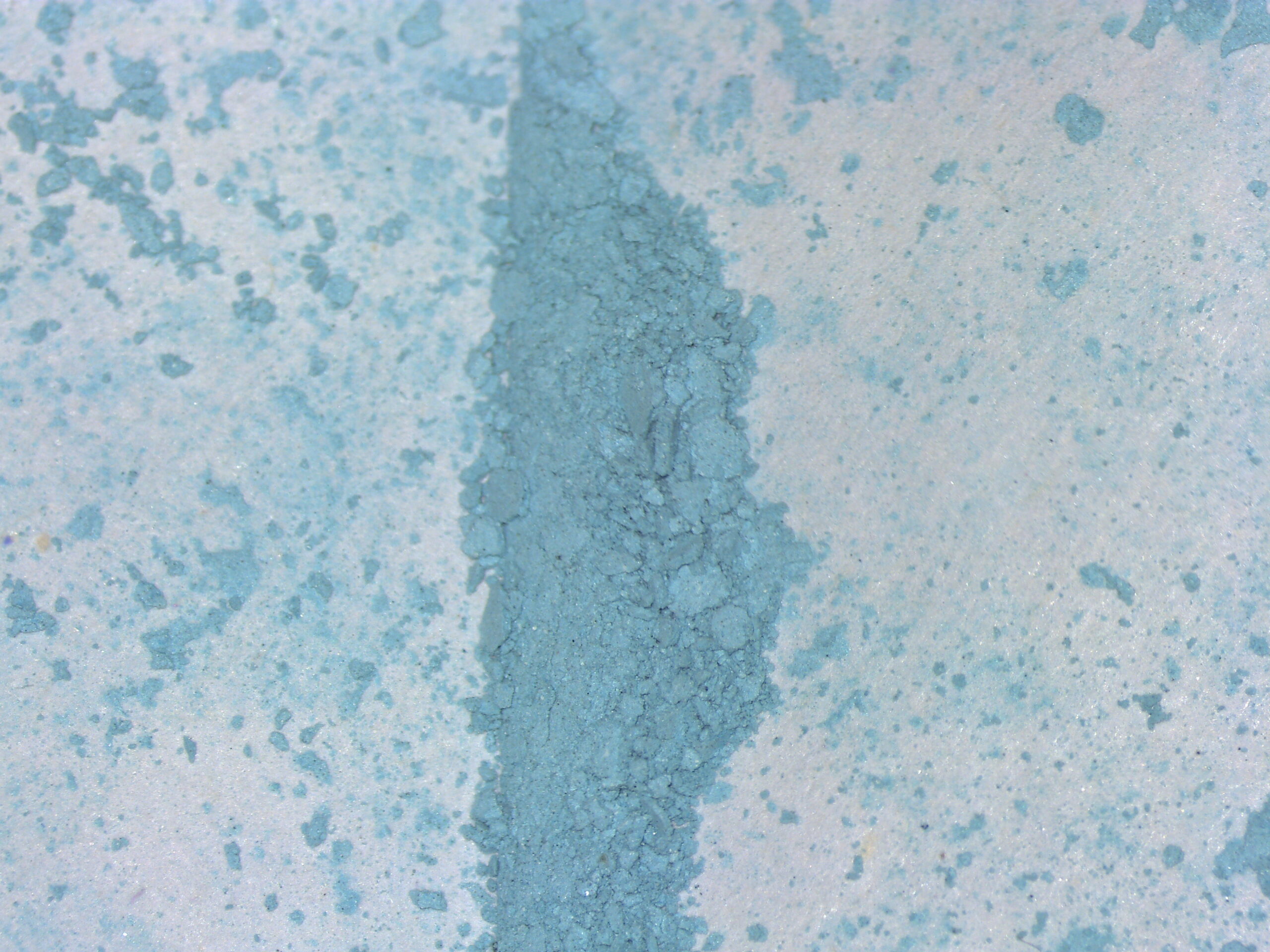

Typical evidence submitted for analysis includes fragments of improvised explosive devices (e.g. pieces of a pipe bomb or circuitry from a detonator), hoax devices (to confirm if any real explosive material is present), suspicious powders or crystals, illicit firework compositions, and propellant powders from ammunition.

Chemical unknowns are submitted to FSI for identification and composition determination. Chemical unknowns can be used in carrying out offences such as assault e.g. acid attacks or criminal damage. After a visual examination of the unknown substance, the qualitative analysis of the compound is completed using FTIR, GCMS, IC, µXRF in addition to wet chemistry techniques such as pH, solubility etc.